Say cheese — and hold very, very still

Two artists have built the world’s largest tintype camera at a photography fair to capture enduring images of British icons — and Nancy Durrant

It’s like magic, really. In this image-saturated world, any mug with a smartphone can snap, crop, filter and instantly share pictures of anything from their lunch to their backside. And yet the miracle of developing a photograph, of watching it appear from the darkness in a bath of reeking chemicals, has lost none of its enchantment. Even so, listening back to the tape of me watching my own face swim into view, first black, then a surprising navy blue, and then suddenly me, in pin-sharp black and brownish-grey, is a bit cringey. “It’s so cool!” I squeal.

Walter Hugo, of the London-based artist duo (and married couple) Walter and Zoniel, who are shooting me for a project they are exhibiting at the Photo London photography fair, assures me that this is normal.

“We did a portrait series in Bethnal Green [in east London] — we got this aspiring drug dealer who came along with his just-out-of-prison murderer friend, a drug dealer. They looked scary and tough, but there’s this one moment when you put the plate in the chemical, everyone becomes like an eight-year-old. The façade drops. It’s my favourite thing.”

Much as I might fancy my half-length portrait going on display in some national museum, in fact my picture — a tintype, one of the earliest forms of photography developed directly on to a sheet of metal and thus a one-off — is really just a test. For Photo London, which opens to the public tomorrow, Walter and Zoniel, both 35, have taken it upon themselves to build the world’s biggest tintype camera.

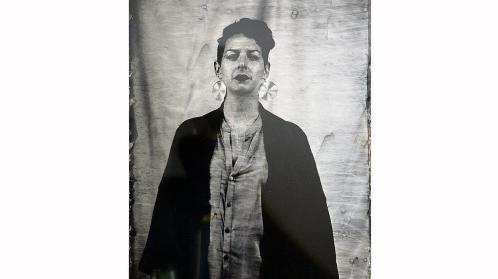

Eddie Redmayne by Walter and Zoniel

In this test, it takes the form of a blacked-out basement room — the walls are the camera box — at the Gazelli Art House gallery in Mayfair. It contains a number of chemical baths, and the only aperture for light, with heavy curtains taped around it, is a huge lens. “It took us three years to find,” says Walter.

The aim is to create the first full-length, life-size tintype photographs. Their subjects, whom they will shoot in a similar but rather tidier set-up at the fair’s base in Somerset House (you won’t have to crawl into the dark room on your hands and knees or stand motionless for 30 seconds in a basement corridor to have your picture taken, as I did), will be “icons of Britain” such as the fashion designer Paul Smith and the model and artist Daphne Guinness.

“We’re trying to do people who are important at this moment, so that it’s like those 17th-century portraits you see at the [National] Portrait Gallery. Like, who the hell was this?” The key appeal of the tintype, explains Walter, is that unlike a conventional printed photograph, “500 years from now, these pieces of metal will still be there”, unchanged and unfaded — more durable even than those now rather puzzling paintings.

The series is the culmination of a group of works that began with 50 ambrotypes (positive prints on glass made with a variation of the wet plate collodion process) made in 2012-13 of their up-and-coming pals (Eddie Redmayne, for example), while they’ve made hand-coloured and gilded prints of celebrities such as Lindsay Lohan, as well as those aforementioned Bethnal Green bad boys.

Walter, a London native, and Zoniel, who grew up mostly in Wales, aren’t photographers as such. They are probably best known for their installation at the Liverpool Biennial in 2014, for which they stealthily filled the windows of a derelict shop in Toxteth with tanks of illuminated jellyfish, then set the metal shutters to open at a certain time every night. Yet it’s not particularly surprising that they return to the medium often in their multimedia artworks.

Walter started out as a scientist, while as a teenager Zoniel, as she puts it, “ran away to a monastery and became a nun”, studying with a Tibetan master in Scotland for a time. That the properties of light and the chemical universe should appeal to them both makes perfect sense, albeit from wildly differing angles.

The public nature of this project is also part of the appeal for the artists. They will create an installation at the fair that will allow people to see how the prints are made (although the works will have been created before the public is allowed in, health and safety not allowing for the sloshing about of hazardous chemicals).

Public art is a strong theme in Walter and Zoniel’s work, from the jellyfish — to which small children were brought in their pyjamas at nightfall by excited Toxteth parents, keen to share with them this magical and, crucially, local event — to a recent project at Tate Britain, Salt Print Selfie. In this they got members of the public to create self-portraits. Each had control of the shutter, but couldn’t see the images (which were projected above their heads) and had to rely on strangers to help them choose one. Then another stranger had to steam each subject’s face to extract the salt, which was then used in the chemical process to make the print – a true self-portrait, made with your own, well, sweat.

“With public art you can have a much stronger relationship with a much greater number of people,” says Zoniel. “For us it’s about that element of engaging people and public art has that ability. We had a discussion here with a lady from the Arts Council — people from institutions see [public art] as a stepping stone to being inside the institution . . .”

500 years from now, these pieces of metal will still be there

“We basically had an argument about where funding goes,” interjects Walter. “Why isn’t there more funding for poor neighbourhoods [like Toxteth]? Why isn’t art placed in those places? Why is it always near a bank, or inside a bank?”

The duo will be returning to Liverpool this year with a catapult, allowing members of the public to hurl biodegradable paint at the outside of the city’s Open Eye Gallery. The idea is to demystify and familiarise what can be an intimidating space, in the hope that it will encourage otherwise reluctant locals to come inside.

“Again, it’s about engaging that sense of mischief, which relates to creativity,” says Zoniel. “If you do anything that’s creative you have to step outside the boundaries of what you’d normally be [doing]. And that’s in everybody. We did a kind of prelude to that [paint] project at the Silicon Valley art fair and there was one guy who came along on opening night, a really serious guy working in the fair, and he’d brought his two little daughters along. And he was like, ‘They can have a go, I’m not having a go’, and I said, ‘Are you sure? I mean you’re standing here.’ And I persuaded him to have a go while he was there with his daughters, and he came back seven times without them.”

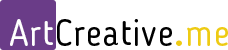

I regard my picture, which, I learn with some regret, will not go on display. The Photo London images will be the end of this particular project, Walter tells me; they’re moving on to other things. Zoniel points out that, with my gold earrings glowing in the warm brownish tinge of the tintype, I look as though I’m “from another era, ancient Egypt maybe”.

It is like peering into some sort of time-travel mirror. I feel momentarily monumental, and slightly awed that this picture could indeed last for ever. “Who the hell is that?” indeed.

Photo London is at Somerset House, London WC2 (photolondon.org), May 19-22. The Liverpool Biennial (biennial.com) runs from July 9 to October 16

Five photographers to watch at the fair

Felicity Hammond, Photographers’ Gallery, London

Hammond’s work doesn’t fit into any box — you’d be likely to call her site-specific work “installation” if it were not in a photography fair. Glossy, seductive but really quite weird, her Language of Living bring the virtual landscape of architects’ renderings into

the real world. Brrr.

Ahmet Polat, x-ist, Istanbul

Polat is a Dutch-Turkish artist and his view as insider and outsider gives his series Kemal’s Dream — looking at the youth of Turkey — a unique perspective. He has described photography as “a slow knife that allows you to get past people’s defence mechanisms”.

Untitled by Dawit L Petros

Dawit L Petros, Tiwani Contemporary, London

A cross between figurative and abstract, the work of this New York-based Eritrean artist considers the subject of African migration, and attempts to liberate it from the European colonial backdrop. Made in cities including Bamako (Mali), Nouakchott (Mauritania) and Dakar (Senegal), they are disquieting and very beautiful.

Zanele Muholi, Yancey Richardson, New York

Muholi, who describes herself as a visual activist, has long charted the complicated journey of the African queer community. Now she has turned the camera on herself, experimenting with characters and archetypes and exploring and challenging the culturally dominant images of black women in the media. The results have a palpable power.

Yoshinori Mizutani’s Sakura

Yoshinori Mizutani, IBASHO, Antwerp

This 28-year-old Japanese artist searches for natural beauty amid the urban flurry of Tokyo. His series Sakura, focusing on the city’s famously glorious cherry blossom, will be on display at the fair. He will also be wandering the streets and parks of London to investigate their natural diversity to create a special portfolio.